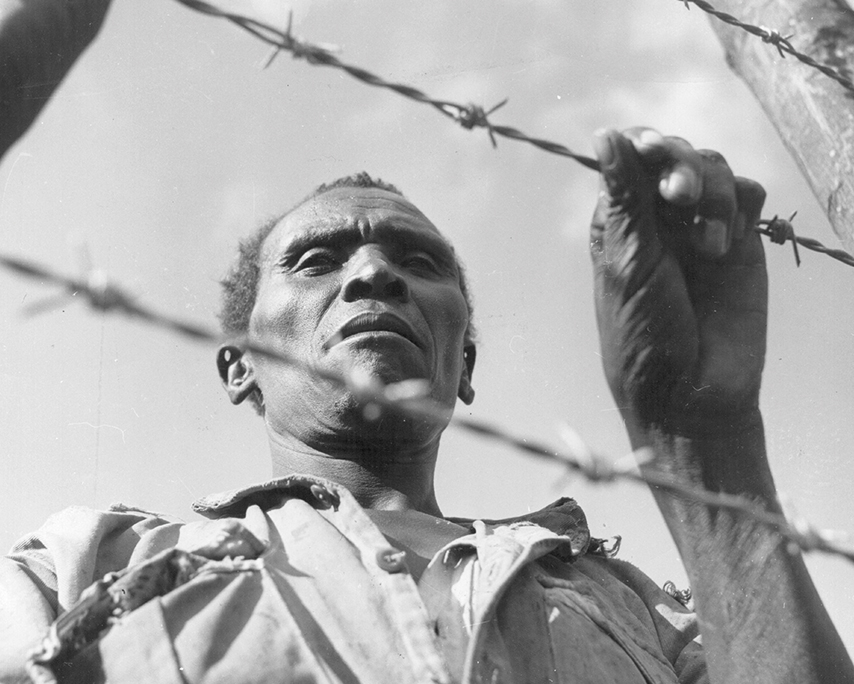

An imprisoned Mau Mau soldier in Kenya.

Photo Credit: Three Lions/Getty Images

International Day of Non-Violence

Conflict and healing in Africa through the lens of philosophy of violence

Wars, revolutions, state repression, and even the subtle harms caused by inequality remind us that violence is never far from the surface of society. The philosophy of violence seeks to go beyond immediate events and ask deeper questions: What is violence? Can it ever be justified? What does it do to people and communities? And what alternatives exist?

At its core, the philosophy of violence examines four major areas. First, it seeks to define what violence actually is. For some, it is limited to physical harm such as assault, war, or murder. For others, violence also includes less visible forms: the poverty, inequality, and exclusion produced by unjust systems, or the harmful cultural beliefs that legitimise discrimination.

Second, it asks whether violence can ever be justified. For instance, self-defence is widely accepted, but what about armed uprisings against tyranny? Can violence lead to liberation, or does it only perpetuate more violence?

Third, the philosophy of violence looks at the consequences of violent acts. Even if they achieve short-term goals, what scars do they leave on individuals and societies? Does violence help build lasting political institutions, or does it destabilise them?

Finally, it explores alternatives. Peacebuilding, reconciliation, and justice processes all raise the possibility that violence is not the only, or even the best, path to change.

In Africa, these philosophical debates take on a concrete and urgent dimension. Colonialism, independence struggles, authoritarian regimes, and ongoing social inequalities have deeply shaped the continent’s modern history.

During colonial rule, Africans endured widespread violence through forced labour, land dispossession, cultural suppression, and military repression. When independence movements emerged in the mid-20th century, many turned to armed struggle as a means of resistance.

In countries like Algeria, Kenya, and Mozambique, violence became a tool of liberation. For many, it was seen not only as necessary but also as a way to reclaim dignity and agency. Yet liberation through violence also left a mixed legacy. On the one hand, it achieved independence. On the other hand, it sometimes laid the groundwork for militarised politics, cycles of revenge, or governments that relied heavily on force.

After independence, violence did not disappear. In some countries, authoritarian leaders used state violence to silence dissent or consolidate power. At the same time, structural violence persisted in the form of poverty, corruption, and unequal access to opportunities. This kind of violence does not always appear in the headlines, but it is deeply felt in everyday life, whether through lack of healthcare, poor infrastructure, or economic exclusion.

Despite these challenges, Africa has also pioneered unique responses to violence. Traditional philosophies such as Ubuntu in Southern Africa emphasise humanity, interconnectedness, and reconciliation. Instead of seeing people as isolated individuals, Ubuntu insists that “a person is a person through other people.” Other countries have developed their own reconciliation processes, blending modern legal approaches with local traditions of dialogue, mediation, and community healing.

In the African context, the philosophy of violence implies several key lessons. First, violence must be understood broadly, not only as war or physical conflict, but also as the structural inequalities and injustices that prevent people from living dignified lives. Second, while violence was sometimes used in the struggle for liberation, its long-term effects show that it is not a sustainable path to justice. Third, the continent’s own philosophies of peace and reconciliation offer powerful alternatives that the world can learn from.

As Africa continues to face challenges such as inequality, corruption, and political instability, the philosophy of violence remains highly relevant. It reminds us that true liberation is not only about breaking free from external control, but also about building societies where dignity, justice, and peace are a reality for everyone.